Photo: Midjourney, Shutterstock

Text by: Gleb King

Natural wines are not a trend anymore. They have passed the peak of hypeness and became one of the rightful categories on the market. Does this mean that we don’t need to care about them? Well, as long as most of us were interested in them for a fair amount of time, there’s no reason to stop being so. Today the concept of natural wines has evolved compared to what we saw 5-6 years ago. For the moment most wine lovers know that sulfur in wine is not dangerous, pesticides are okay and cultural yeasts help winemakers to perform better. You can’t impress anyone with a horse manure put in a horn and dug 6 feet under at the specific phase of the moon. What we really care about – put away all the theater – how is the wine? And yes, the same as with classic winemaking, on the natural wine’s scene there are some ugly clowns and some noble Don Juans. To sort one from another, we wrote this article – and strengthened it with real examples of some decent natural wines that have already earned their well respected position on the market.

Organic

This is a huge category and it takes most of the wines from this article under its wing. But nevertheless we made it a solo subparagraph – mostly because there are some wines that, in general, follow classic winemaking rules, but somewhere break them and go natural. For example – this famous chardonnay from California uses organically grown grapes but mostly goes through classic winemaking processes. Another good example is Chateau Ausone, which is not officially certified organic but practices organic farming methods in its vineyards: avoid the use of synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers and instead rely on natural methods to manage pests and fertilize the soil. You may guess from the name of this category – organic – that the main natural impact here comes from counteracting with soil on the vineyard.

Winemakers use ladybugs in vineyards as a natural method of pest control, especially to combat aphids and other soft-bodied insects that can damage grapevines. Ladybugs, or ladybird beetles, are beneficial insects that play a crucial role in maintaining a healthy and balanced vineyard ecosystem.

Biodynamic

Okay, here is something serious. The winemakers who are into the biodynamic category tend to think that there’s no use to bother nature doing it’s natural thing. They believe that phases of the moon impact the grape growing cycles and that sulfur – the main modern wine preservative – is just a crotch for an ill wine – the healthy one doesn’t need it. Some of them even go deeper and treat winemaking almost as a religion. The roots of this approach can be traced back to the early 20th century, when Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner developed the principles of biodynamic agriculture in 1924. However, it wasn't until the 1960s that biodynamic winemaking began to gain traction in France, with pioneers like Eugène Meyer in Alsace and Nicolas Joly in the Loire Valley. There is a good way to know if the producer is really biodynamic or not – you may Google if it has a Demeter certification – most of them are there, with some exceptions.

«Yes, the winery may be biodynamic and not organic. In some cases, wineries may choose not to pursue organic certification but still adhere to biodynamic principles».

Both organic and biodynamic

This category is really rare because to be there you have to follow a lot of rules. Really a lot. The wine entrepreneurs that work in this category may be either young and hip artists or the old-time legends. In the first case – they are not focused on wide recognition, and in the second – they already have it. Organic and biodynamic way is the hardest one for mass-production because there you can’t rely on modern science achievements. Either mother nature does everything on herself or not. Those winemakers are also philosophers and romantics. One of the most popular producers of this kind and also, which is very symbolic, the producer of the most expensive wine in the world – is Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. Another good example is Lalou-Bize-Leroy who, being 92 years old, still runs her organic and biodynamic winery Domaine Leroy.

Jean-Pierre Robinot is an iconic natural winemaker. This wine is particularly worth attention because it’s a Loire’s rose pet-nat from Chenin Noir (or Pineau d’Aunis). This is a sparkling rose wine with white pepper and red berries on the nose. Sealed classically under crown-cap.

Pet-Nat and Glou-Glou

There are two main qualities that unify these two categories: these wines are low in alcohol and very hip. If you find a wine bar without those on the list – you’re in past, look for a copy of yourself and try to make amends for your future. Speaking about wines – Pet-Nat, short for Pétillant Naturel (French for "naturally sparkling") – is a style of sparkling wine made using the ancestral method of fermentation. This is one of the oldest techniques for making sparkling wine – just start the fermentation and don’t wait until it ends – capture the wine in the bottle and it will carbonate itself. Pet-Nats are often unfiltered, which can result in cloudiness due to the yeast sediment. They have a raw, rustic character and in most cases are sealed with a crown cap (like beer).

«If you find a wine bar without those on the list – you’re in past, look for your copy and try to make amends»

Glou-Glou wines (pronounced "gloo-gloo") are a category of wines prized for their lightness, drinkability, and fun character. The term is French, mimicking the sound of gulping or glugging wine, and is often used to describe wines that are easy to drink and not overly complex. Many Glou-Glou wines are made by producers who follow natural winemaking practices: organic or biodynamic farming, native yeast fermentation, low or no added sulfites, and minimal filtration.

A qvevri is typically egg-shaped fermenter made of terracotta (fired clay), which allows for some natural oxygen exchange during fermentation. Grapes, including their skins, seeds, and sometimes stems (known collectively as "must"), are placed directly into the qvevri after being crushed. The qvevri winemaking method is considered one of the oldest in the world, with archaeological evidence dating back over 8,000 years. In 2013, UNESCO recognized traditional Georgian qvevri winemaking as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

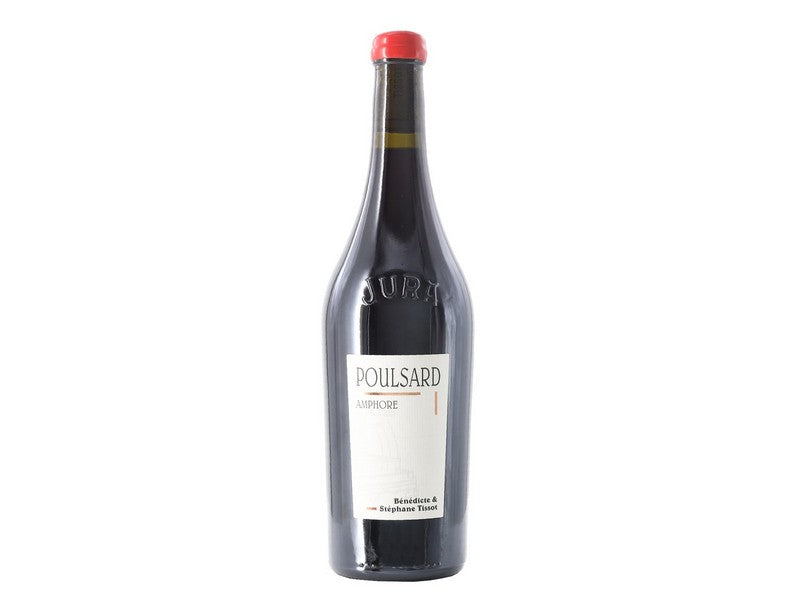

Orange and amphorae experiments

Orange wines are a type of white wine made by fermenting white grapes with their skins and seeds, a process more commonly associated with red wine production. This skin contact gives the wine its unique color, which ranges from pale amber to deep orange, as well as distinct flavors and textures. Orange wine has ancient origins, particularly in Georgia, where winemakers have been using this method for thousands of years. In Georgia, orange wines are traditionally fermented in large clay vessels called qvevri, buried underground.

«Qvevri is a kind of amphora but very specific and Georgian. In the bordering Armenia those are called karases – so – their naming is a matter of origin».

Qvevri is a kind of amphora but very specific and Georgian. In the bordering Armenia those are called karases – so – their naming is a matter of origin, but the form-factor is almost the same. The modern revival of orange wine started in the late 20th century, especially in regions like northeastern Italy (Friuli-Venezia Giulia) and Slovenia, and it has since spread worldwide. Apart from making an orange wine, fermentation inside amphoras – is one of the modern winemaker’s instruments. There are also some red, rose and sparkling wines, made in this fashion.