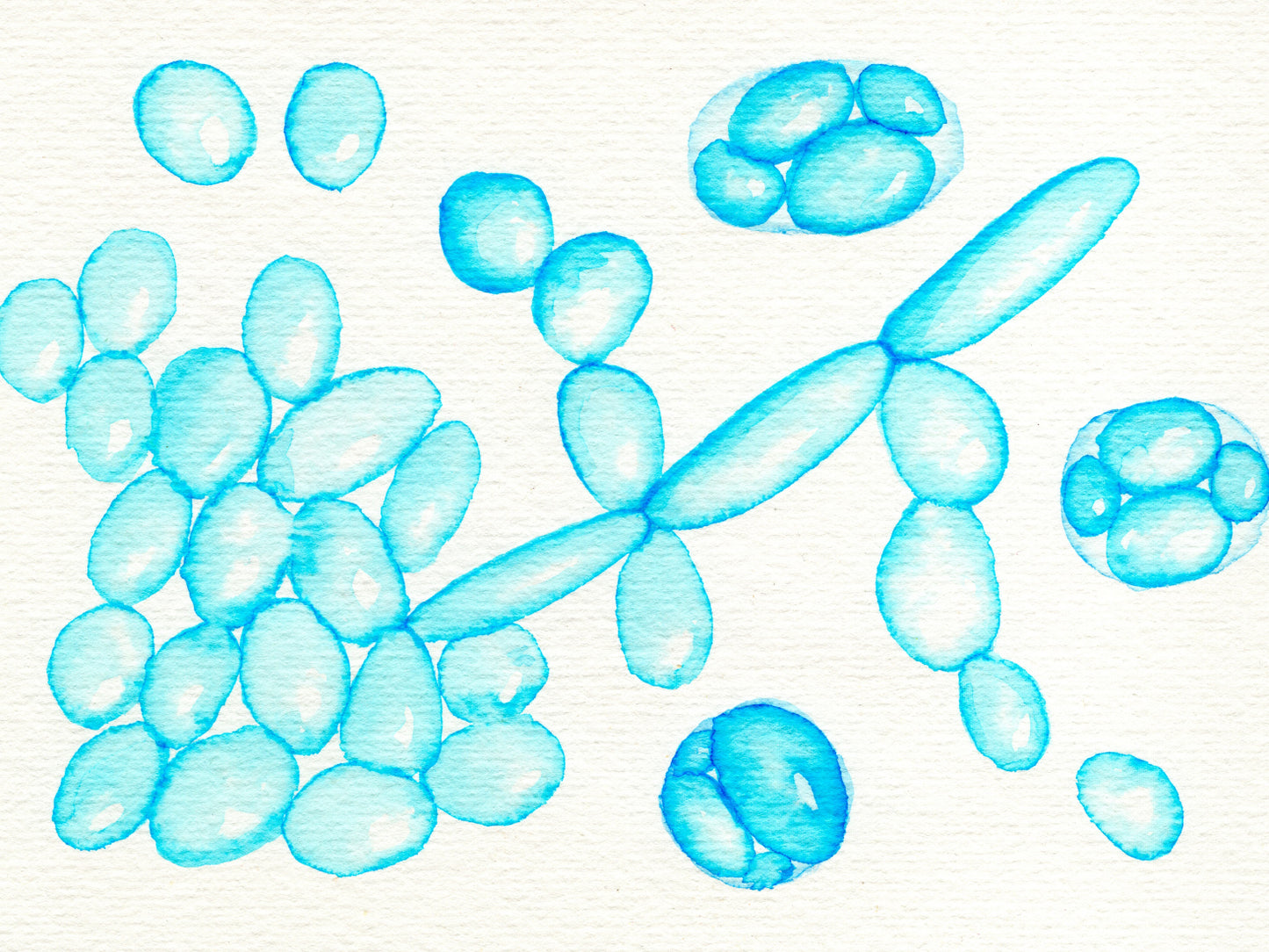

Photo: Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast strain

Credit to photo: Shutterstock/Kateryna Kon

Text by: Gleb King

You can’t underestimate the role of yeasts in wine. Literally, without them it won’t exist. Neither the bread, cheese, yogurt and pickles, but here we narrow down our focus to wines. And while they keep on working on thousands of wineries right now, eating sugar and pooping alcohol, let’s look at them closer and have a little yeast enlightenment lesson. The following 5 facts will help you understand what they are, how they work and why they make wine for us.

Single-celled alcohol makers

Yeasts are single-celled funghi. Yes, they are from the same family as porcini, and they go with aged Chardonnay even better – they make it. The most commonly used strain of yeast for wine fermentation is called Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It is known for its efficiency in converting sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. This strain is particularly favored for its ability to withstand high alcohol levels and its tolerance to sulfur dioxide, which is often used in winemaking.

T-1000 is here

This is where winemakers add tropic stuff to your white wine. Yeasts not only convert sugars to alcohol but also produce various byproducts that contribute to aroma and flavor of wine. These byproducts include esters, phenols and higher alcohols, which enhance the complexity and character of the final product. For example, for aromatic variety of Sauvignon Blanc, the winemakers sometimes use special strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, that help ferment out and amplify the sauvignon’s famous tropic and blackcurrant aromas. One of the best examples of such wines is Clos Henri Sauvignon Blanc from Marlborough, New Zealand. Sommeliers know that very aromatic sauvignons were made with a little help of:

– Ec169. Specific strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that is favored for aromatic white wines, including Sauvignon Blanc. It can enhance the wine's varietal character and aromatic profile, bringing out the fruity and floral notes typical of this grape.

– QA23: This yeast strain is often used for Sauvignon Blanc due to its ability to enhance the wine's tropical fruit aromas and contribute to a balanced mouthfeel. It's known for producing wines with vibrant acidity.

– K1 V1116: Another yeast strain that's commonly used in Sauvignon Blanc production. It is particularly effective at fermenting at lower temperatures and is known for enhancing the varietal's aromatic complexity and freshness.

Wild yeast eats a chocolate

Where the wild things are

Actually, yeasts are everywhere – even in the air we breathe. It’s also on grape’s skins and leaves and elsewhere in the vineyard. To start the fermentation process, the winemaker may add some yeasts in the wine or not – the yeasts from nature will find sugar and pick up their burden. So, if you leave a sweet juice in a warm place – the wine is unavoidable. In addition to cultivated yeasts, wild or spontaneous fermentation can occur when natural yeasts present on grapes or in the environment are allowed to ferment the wine. This can lead to unique flavor profiles, but it also introduces an element of unpredictability in the fermentation process. Those wild yeasts today are very hip – they go well with ecotrends – no yeast production facilities, no carbon footprint. Though, most winemakers still tend to keep it old-school and control the fermentation. Chavost Estate from Champagne makes wine using spontaneous fermentation with indigenous yeast.

Keep it cool

Yeasts have an optimal temperature range for fermentation, typically between 55-85°F (13-29°C). At lower temperatures, yeast activity is slower, which can lead to a longer fermentation process and the development of more complex flavors. The temperature at which fermentation occurs significantly affects the final wine. Cooler fermentation temperatures (around 55-65°F or 13-18°C) are often used for white wines to retain fruity and floral aromas, while warmer fermentation (between 70-85°F or 21-29°C) is common for red wines, helping to extract color and tannins from the grape skins. When fermentation temperatures exceed certain thresholds, yeasts can become stressed. Stress can lead to stuck fermentations, where the yeast stops working before all the sugars are converted to alcohol.

Sparkle-sparkle

Yeast fermentation typically occurs in two phases: the lag phase and the exponential phase. During the lag phase, yeast cells acclimate to their environment and begin to multiply, while in the exponential phase, they rapidly convert sugars to alcohol, producing carbon dioxide as a byproduct until the sugars are depleted or the alcohol concentration becomes too high for the yeast to survive. This CO2 is very useful – it prevents the wine from oxidation, naturally pushing out all the oxygen from top of the vat. And if the fermenter is airtight – then it’s time for sparkling wine! In the case of Champagne making, the CO2-producing fermentation happens straight in the bottle.