Credit to photo: Shutterstock/barmalini; Kinife

Text by: Gleb King

Champagne is religion. Champagne is big business. Also, it’s tears. Whatever may cause them – the breakup, the celebration of any kind, the price of a bottle – Champagne is meant to bring emotions. Also, it’s the most romanticized, glamourized, art-inspiring alcoholic drink in the world. And yes, there are many copies of Champagne – the technology is known and googled, there’s no need to send a spy to Reims to make pencil sketches. In South Africa, for example, champagne-inspired sparklings are called MCCs (Méthode Cap Classique) and in Italy they are Franciacortas. In Spain they are Cavas and in Germany they are Sekts. All of them may even be more complex and bubbly than original Champagne, but they can’t bear its name. Only sparkling wines from north-eastern France, from provinces of Aube, Côte des Blancs, Côte de Sézanne, Montagne de Reims, and Vallée de la Marne, may be called Champagne. Not to mention, they have to follow all the rules of Champagne AOC, regulated by Comité de Champagne. Champagnes (same as all the other Champagnewise made wines across the world) are made using a specialized process known as the méthode champenoise (traditional method), which is distinct from other winemaking techniques due to its focus on secondary fermentation in the bottle.

It’s Majesty, The Metode Champenoise

Harvesting

Champagne is typically made from three main grape varieties: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier. Chardonnay adds elegance, Pinot Noir provides structure, and Pinot Meunier contributes fruitiness. Grapes are hand-harvested to prevent damage, ensuring that only the best, undamaged fruit is used.

Pressing

The grapes are gently pressed to extract the juice, with minimal contact between the juice and skins, especially for the red grape varieties (Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier). This helps to produce a light-colored juice. The juice from the first pressing (known as the cuvée) is of the highest quality and is used to make premium Champagne. The second pressing (the taille) is often used for less prestigious wines.

Primary Fermentation

The juice undergoes its first fermentation, where natural sugars are converted into alcohol. This results in a still wine (no bubbles), called the vin clair. The base wine is dry and high in acidity, characteristics essential for producing Champagne. On this stage the wine is very acidic and literally undrinkable – it’s a raw material for future Champagne. Champagne making has always been an art of blending. After primary fermentation, different base wines are mixed. This can include different grape varieties, vintages, or vineyards to create a consistent style. For non-vintage Champagne, wines from different years are blended together. Vintage Champagne uses only grapes from a single exceptional year.

Secondary Fermentation

A mixture of sugar, yeast, and a small amount of wine (called liqueur de tirage) is added to the blended base wine, which is then bottled and sealed with a temporary cap (crown cap). This induces a second fermentation inside the bottle. During the second fermentation, the yeast consumes the added sugar and produces alcohol and carbon dioxide (CO₂), which creates the bubbles (effervescence) that Champagne is known for. Since the CO₂ is trapped in the sealed bottle, it dissolves into the wine, creating pressure.

Aging on the Lees

After the second fermentation, the wine is aged in the bottle with the dead yeast cells (called lees) for at least 15 months (for non-vintage Champagne) or 3 years (for vintage Champagne). Some premium Champagnes are aged for even longer. This aging process imparts complexity and creaminess to the wine, giving it toasty, nutty, and brioche-like flavors.

Riddling (Remuage)

After the aging period, the dead yeast cells must be removed. This is done through a process called riddling. The bottles are gradually tilted and rotated over time, allowing the sediment to collect in the neck of the bottle. Riddling was traditionally done by hand using riddling racks, but today, it is often done mechanically with devices called gyropalettes.

The process of opening the cap to get rid of the sediment after secondary fermentation (disgorging).

Disgorging (Dégorgement)

Once the sediment has collected in the neck, the neck of the bottle is frozen, creating a small ice plug that contains the lees. The bottle is then opened, and the pressure from the carbonation forces the ice plug out, leaving clear Champagne behind. Some wine is lost during disgorgement, so it needs to be topped up before sealing.

Dosage

After disgorging, a mixture of sugar and wine (called the liqueur d’expédition) is added to adjust the sweetness level of the Champagne. The amount of sugar determines the style:

Brut Nature: No added sugar (bone dry). 3 grams per liter (g/l)

Extra Brut: Very little sugar (extra dry). 0-6 g/l

Brut: The most common style, slightly dry. 0-12 g/l

Extra Dry: A bit sweeter than Brut. 12-17 g/l

Sec: More sweetness. 17-32 g/l

Demi-Sec: Almost desert sweetness. 32-50 g/l

Doux: A treat. 50 g/l

Final Bottling and Aging

After the dosage is added, the bottle is sealed with the final cork (secured with a wire cage called a muselet) and labeled. Some Champagnes are aged further in the bottle after disgorgement to enhance their complexity and allow flavors to meld.

Champagne bottles in the cellar on special racks, collecting the sediment (Remuage).

How much pressure is inside?

Though a standard Champagne bottle holds a pressure of 5-6 atmospheres, which is about 5 kg per centimeter, today it has much less chance to self-explode. Anyway, it’s still dangerous. The opening of a champagne bottle is a complex supersonic phenomena. According to this article, an unchained cork flies relatively slow – about 20 meters per second, but the CO2’s speed is around 400 meters per second which is faster than the speed of sound. The gas literally breaks the sound barrier.

Kinds of Champagne

Non-vintage – a mixture of wines of different vintages. This category is a welcoming face of a Champagne house. It’s believed to show the style of the brand.

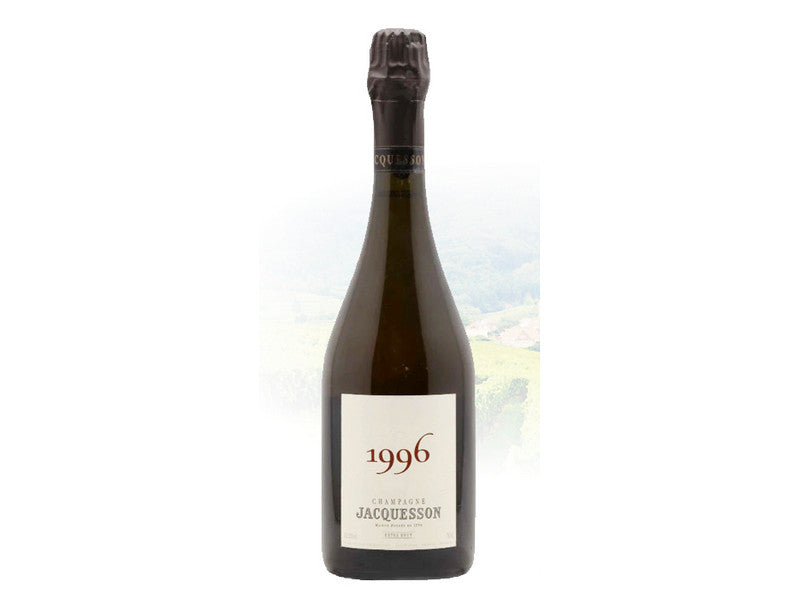

Vintage (Millesime) – a wine of one year’s harvest. Vintage Champagne is unique expression of weather conditions of each year. It’s made only when the vintage is perfect and worth playing solo.

Blanc de Blancs – Champagne, made only of white grape varieties. Mostly it’s Chardonnay.

Blanc de Noirs – a white wine, made of red grape varieties – usually – Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier.

Rosé – rose Champagne. May be whether vintage or non-vintage, or even – Cuvee de Prestige.

Cuvée de Prestige – the highest level of Champagne fine art, the main wine of a Champagne house. Made only at the best vintages, or is a blend of several ones. The long sediment aging is typical for them. The most known examples – Louis Roederer Cristal, Billecart-Salmon Cuvee Elisabeth Salmon Rose, Drappier Grande Sendree, Moet Chandon Dom Perignon, Perrier-Jouet Belle Epoque or Cuvee William Deutz.

Single Vineyard Champagne – this category was recently made famous by Récoltants – small Champagne houses, making wines only from their own vineyards. But also is produced by grand Champagne houses. One of the greatest examples is Krug Clos d'Ambonnay.